Memory

Our memory research has focused on naturalistic expressions of memory, particularly autobiographical memory, which refers to processing of information concerning events and facts from one's past. We seek to attain convergent results by using multiple methods of investigation (e.g., psychological testing, neuroimaging) across healthy and clinical samples.

Assessment of autobiographical memory

This research was initially inspired by patient M.L., who had amnesia specific to autobiographical episodes following a traumatic brain injury (Levine et al., 1998, 1999; Levine et al., 2009). From 2000-2010, our work was largely focused on analysis of the behavioral and neural correlates of autobiographical memory in various clinical samples as well as healthy younger and older adults.

Much of this work utilized the Autobiographical Interview (Levine et al., 2002), now widely used for quantification of detail recovery in response to specific cues. In the past 10 years, we have developed methods for prospectively collecting events for later testing or brain imaging, including staged events. We applied similar methods to assess behavioural and brain measures in relation to memories of a traumatic airline flight in which disaster was narrowly averted. To learn more about this research, read the sections below on this page.

Individual differences and Severely Deficient Autographical Memory (SDAM)

In the course of this work, we were contacted by individuals with who reported an inability to consciously retrieve and subjectively experience personal past events in the absence of a clinical pathological condition, a condition we labelled Severely Deficient Autobiographical Memory (SDAM; Palombo et al, 2015). The discovery of SDAM prompted us to investigate the spectrum of individual differences in autobiographical memory in healthy adults using the Survey of Autobiographical Memory (SAM; Palombo et al., 2013).

To read more, check out our individual differences and SDAM page.

Our memory research has focused on naturalistic expressions of memory, particularly autobiographical memory, which refers to processing of information concerning events and facts from one's past. We seek to attain convergent results by using multiple methods of investigation (e.g., psychological testing, neuroimaging) across healthy and clinical samples.

Assessment of autobiographical memory

This research was initially inspired by patient M.L., who had amnesia specific to autobiographical episodes following a traumatic brain injury (Levine et al., 1998, 1999; Levine et al., 2009). From 2000-2010, our work was largely focused on analysis of the behavioral and neural correlates of autobiographical memory in various clinical samples as well as healthy younger and older adults.

Much of this work utilized the Autobiographical Interview (Levine et al., 2002), now widely used for quantification of detail recovery in response to specific cues. In the past 10 years, we have developed methods for prospectively collecting events for later testing or brain imaging, including staged events. We applied similar methods to assess behavioural and brain measures in relation to memories of a traumatic airline flight in which disaster was narrowly averted. To learn more about this research, read the sections below on this page.

Individual differences and Severely Deficient Autographical Memory (SDAM)

In the course of this work, we were contacted by individuals with who reported an inability to consciously retrieve and subjectively experience personal past events in the absence of a clinical pathological condition, a condition we labelled Severely Deficient Autobiographical Memory (SDAM; Palombo et al, 2015). The discovery of SDAM prompted us to investigate the spectrum of individual differences in autobiographical memory in healthy adults using the Survey of Autobiographical Memory (SAM; Palombo et al., 2013).

To read more, check out our individual differences and SDAM page.

The Autobiographical Interview

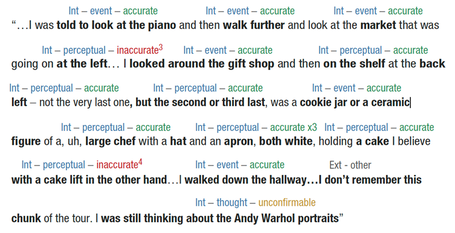

The Autobiographical Interview (AI; Levine et al., 2002) is a method of assessing autobiographical memory using a text-based analysis of transcribed autobiographical protocols. The key innovation of the AI method lies in the segmentation of details into categories for quantification from within a single naturalistic narrative. Internal or episodic details pertain to the description of the event and sensory or mental state details specific to the event. External details pertain to semantic or factual statements and other details not specific to the event.

The AI has been used in over 375 studies. It has proven useful to test theories concerning the nature of memory loss in patients with medial temporal lobe damage (Addis et al., 2007; Rosenbaum et al., 2008; St.-Laurent et al., 2009, Miller et al., 2020), including the seminal case of Henry Molaison (patient H.M.; Steinvorth et al., 2005). It has also been used to characterize naturalistic mnemonic deficits in mild cognitive impairment (MCI; Murphy et al., 2008), aging and neurodegenerative disease (for review, see Simpson et al., 2023), traumatic brain injury (Esopenko & Levine, 2017) and depression (Söderlund et al., 2014).

Other studies have adapted the AI for assessment of autobiographical memory in typical and atypical development (Willoughby et al., 2012; Gascoigne et al., 2013) and in thinking about the future (Addis, Wong, & Schacter, 2008). Numerous studies have demonstrated a relationship between internal (episodic) details as measured by the AI and structural and functional measures of the medial temporal lobes (in addition to patient studies noted above, see Hodgetts et al., 2017; Memel et al., 2020; Palombo et al., 2018).

To view a list of studies using the AI, click here.

The AI has been used in over 375 studies. It has proven useful to test theories concerning the nature of memory loss in patients with medial temporal lobe damage (Addis et al., 2007; Rosenbaum et al., 2008; St.-Laurent et al., 2009, Miller et al., 2020), including the seminal case of Henry Molaison (patient H.M.; Steinvorth et al., 2005). It has also been used to characterize naturalistic mnemonic deficits in mild cognitive impairment (MCI; Murphy et al., 2008), aging and neurodegenerative disease (for review, see Simpson et al., 2023), traumatic brain injury (Esopenko & Levine, 2017) and depression (Söderlund et al., 2014).

Other studies have adapted the AI for assessment of autobiographical memory in typical and atypical development (Willoughby et al., 2012; Gascoigne et al., 2013) and in thinking about the future (Addis, Wong, & Schacter, 2008). Numerous studies have demonstrated a relationship between internal (episodic) details as measured by the AI and structural and functional measures of the medial temporal lobes (in addition to patient studies noted above, see Hodgetts et al., 2017; Memel et al., 2020; Palombo et al., 2018).

To view a list of studies using the AI, click here.

Staged events

Psychological research on memory is historically dominated by laboratory methods – such recognition of words presented by the experimenter – that are precisely controlled but bear little resemblance to real-life. Memory for autobiographical episodes is more ecologically-valid than memory for materials in the laboratory, yet the lack of experimental control over critical event features such as importance, repetition, or accessibility poses experimental limitations relative to laboratory methods.

We have sought to bridge this gap by creating real-world events, allowing us to pair methodological rigor with naturalistic memory assessment. Led by Drs. Nick Diamond and Mike Armson, we began with proof-of-concept exercises to establish the validity of the testing platform and the relationship of staged-event data to laboratory memory test performance. These were followed more recently by investigations of free recall, memory accuracy, and mechanisms supporting spatial and temporal organization in younger and older adults.

We have sought to bridge this gap by creating real-world events, allowing us to pair methodological rigor with naturalistic memory assessment. Led by Drs. Nick Diamond and Mike Armson, we began with proof-of-concept exercises to establish the validity of the testing platform and the relationship of staged-event data to laboratory memory test performance. These were followed more recently by investigations of free recall, memory accuracy, and mechanisms supporting spatial and temporal organization in younger and older adults.

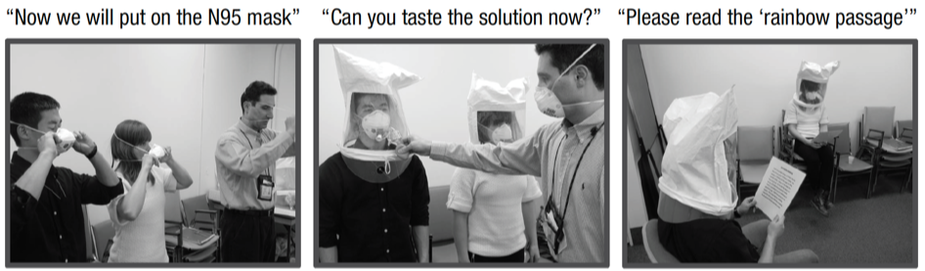

The Baycrest Mask Fit Test

Memory researchers require knowledge of event characteristics and consistency across participants in order to develop unbiased tests. This is usually not possible for naturalistic events, which are idiosyncratic. Researchers have previously turned to "flashbulb" events (e.g., the Challenger disaster, September 11, 2001) to find events with known sequences experienced by large groups of people. As these events are highly emotional and generally rehearsed through media exposure or conversation, they do not generalize to everyday events. (For more on an alternative "diary" method of prospective event collection, see below.)

Starting in 2003 with the SARS epidemic, Ontario hospital employees – including us at Baycrest – were required to undergo a respiratory mask-fitting test. As a scripted medical procedure it met criteria as a standardized event, experienced consistently from one person to the next. Although it was unusual, it was neither emotional nor reactivated in memory through rehearsal.

We tested recognition memory for elements the Mask Fit Test in 135 Baycrest employees (Armson, Abdi, & Levine, 2016). We found that performance obeyed known laws of memory decay, even years post-event, providing proof-of-principle that it is possible to derive a valid test of memory from a staged event.

Starting in 2003 with the SARS epidemic, Ontario hospital employees – including us at Baycrest – were required to undergo a respiratory mask-fitting test. As a scripted medical procedure it met criteria as a standardized event, experienced consistently from one person to the next. Although it was unusual, it was neither emotional nor reactivated in memory through rehearsal.

We tested recognition memory for elements the Mask Fit Test in 135 Baycrest employees (Armson, Abdi, & Levine, 2016). We found that performance obeyed known laws of memory decay, even years post-event, providing proof-of-principle that it is possible to derive a valid test of memory from a staged event.

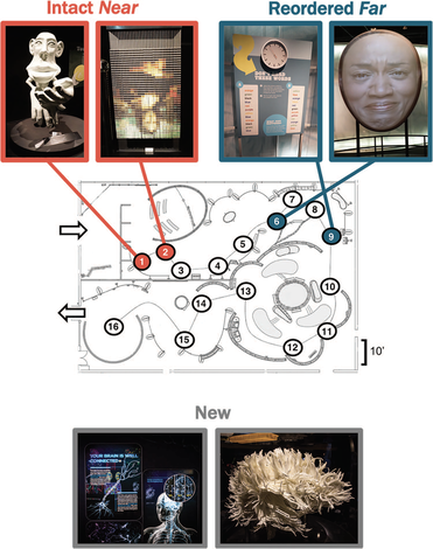

Memory for "Brain: The Inside Story": an exhibit at the Ontario Science Centre

|

The Ontario Science Centre is one of the most popular attractions in Ontario with over 1 million visitors each year. In 2014, the Centre mounted a touring exhibition about the brain. We invited visitors to complete a brief paper and pencil scavenger hunt through the exhibit, ensuring that exposure to the test items was consistent for future testing.

Those who successfully completed the scavenger hunt were invited to participate in an online study 2-4 months later. We were interested in memory for temporal order, which is a more challenging and refined measure of episodic memory than simple true/false recognition (as in the Mask Fit Test). We presented photographs side-by-side, and asked them to judge whether they were in the correct or incorrect order (according to the original sequence) or new (from a separate museum exhibit about the brain). One advantage of testing in this context was our ability to involve adults across the adult age range (as opposed to just younger or older adults, as is usually the case in studies recruiting out of university laboratories). In 141 people aged 18-85, we found that patterns of age-related memory change that were inconsistent with those established in prior laboratory studies, highlighting the importance of testing theories of memory in real life conditions (Diamond, Romero, Jeyakumar, & Levine, 2018). |

The Baycrest Tour

The Mask Fit and Ontario Science Centre studies were useful to establish that staged event methods create a reliable platform for memory assessment across the adult lifespan, yet as they were staged by others, we had little control over the participant selection, materials, or event characteristics. Dr. Nick Diamond developed an audio-guided event, the Baycrest Tour, a museum-style tour of artworks and other objects at Baycrest, for use in our subsequent staged event work.

Direct comparison of naturalistic vs. lab events in assessing age-related memory changes

It was already known that naturalistic (real-life) and laboratory (e.g., word lists) memory tests can produce divergent results. To compare these testing methods on a level playing field, we created slideshow version of the Baycrest tour, presented with the same audioguide as used for the naturalistic version, matching the two events for superficial characteristics such as duration and narrative encoding.

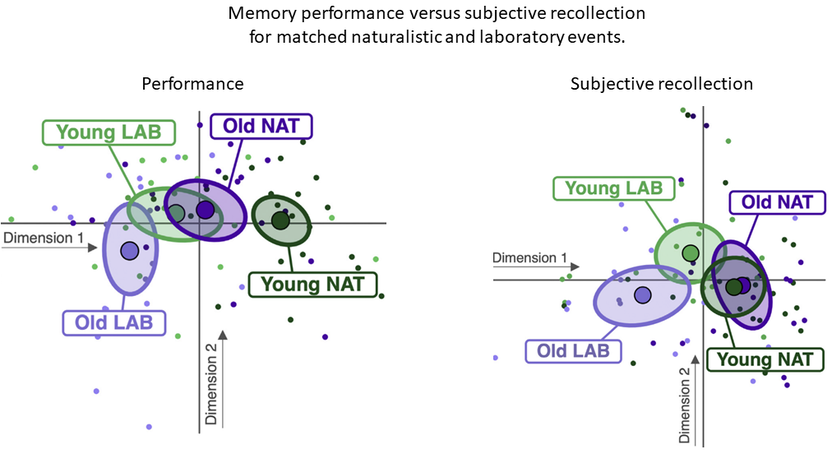

After 48 hours, performance as assessed by true/false statements ("Al Green's statue called ‘The Sage’ is green”) was better for the naturalistic as compared to the laboratory version of the event, confirming that naturalistic encoding boosts memory performance. This advantage held for both younger and older adults. We also asked participants to rate their subjective experience of recollection in response to each item. As expected, older adults' ratings were lower than those of younger adults for the laboratory event, yet their ratings for the naturalistic event were similar to those of younger adults. This suggested that for older adults, memory ratings and memory performance were decoupled – but only for the naturalistic event, possibly due to age-related changes in strategies or memory monitoring abilities (Diamond, Abdi, & Levine, 2020). These findings suggest that laboratory memory tests cannot be held as proxies for real-life memory, especially in older adults.

Direct comparison of naturalistic vs. lab events in assessing age-related memory changes

It was already known that naturalistic (real-life) and laboratory (e.g., word lists) memory tests can produce divergent results. To compare these testing methods on a level playing field, we created slideshow version of the Baycrest tour, presented with the same audioguide as used for the naturalistic version, matching the two events for superficial characteristics such as duration and narrative encoding.

After 48 hours, performance as assessed by true/false statements ("Al Green's statue called ‘The Sage’ is green”) was better for the naturalistic as compared to the laboratory version of the event, confirming that naturalistic encoding boosts memory performance. This advantage held for both younger and older adults. We also asked participants to rate their subjective experience of recollection in response to each item. As expected, older adults' ratings were lower than those of younger adults for the laboratory event, yet their ratings for the naturalistic event were similar to those of younger adults. This suggested that for older adults, memory ratings and memory performance were decoupled – but only for the naturalistic event, possibly due to age-related changes in strategies or memory monitoring abilities (Diamond, Abdi, & Levine, 2020). These findings suggest that laboratory memory tests cannot be held as proxies for real-life memory, especially in older adults.

Left: Older adults (purple) had lower memory performance for the both naturalistic (NAT) and laboratory (LAB) versions of the same event. Note that for both groups, recognition memory performance was higher in the naturalistic version.

Right: Older adults had lower subjective recollection for the laboratory version, but not for the naturalistic version, suggesting that subjective recollection decoupled from performance for the naturalistic event.

From Diamond, Abdi, & Levine (2020)

Extemporaneous (free) recall of the Baycrest Tour

Sample free recall narrative with coding indicating detail classification using the Autobiographical Interview (Levine et al., 2002), augmented by accuracy coding.

Participants’ free recall was highly accurate, regardless of age and time elapsed (which ranged up to 3 years after the event), although forgetting (omissions) was high.

In response to a survey, both memory experts and other academics predicted much lower performance, suggesting that both experts and educated non-experts are overly pessimistic about the accuracy of memory.

Read more about this research from this Baycrest news release and Discover Magazine).

|

How accurate is memory?

We next turned to free recall – the normal narrative process of talking about past events, as done with the Autobiographical Interview. One criticism of the Autobiographical Interview when applied to recall of remote events is that it is impossible to verify the accuracy of recalled details where the ground truth is unknown. By pairing the known event sequence of staged events with the narrative analysis methods of the Autobiographical Interview, we were able to investigate the accuracy of free recall (Diamond, Armson, & Levine, 2020). The prevailing view among memory researchers – and people in general – is that memory is inaccurate. In contrast to this view, we found that free recall of the Baycrest tour was highly accurate in both younger and older adults, even years after initial exposure to the event. |

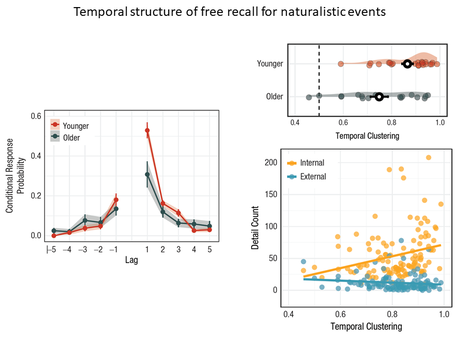

Conditional response probability curves (left) and temporal structuring measures (right) reflect the degree to which the order of freely recalled items follow a consecutive order (relative to original presentation). These measures are widely used in laboratory research using word lists but not to real-life memory because the original sequence of events is generally not available at the time of testing. We found that the temporal structure in free recall of staged events (the Baycrest tour and Mask Fit Test) followed showed expected age sensitivity and predicted the overall richness (internal details) of recall.

Conditional response probability curves (left) and temporal structuring measures (right) reflect the degree to which the order of freely recalled items follow a consecutive order (relative to original presentation). These measures are widely used in laboratory research using word lists but not to real-life memory because the original sequence of events is generally not available at the time of testing. We found that the temporal structure in free recall of staged events (the Baycrest tour and Mask Fit Test) followed showed expected age sensitivity and predicted the overall richness (internal details) of recall.

Free recall dynamics of real-life events in young and old

Research concerning the way people spontaneously jump from one bit of information to another when searching memory has been highly influential in theories of memory, yet this work has been constrained to studies of word lists where the sequences could be controlled and repeated. The degree to which this research generalizes to real-life was unknown.

Using the staged event, Dr. Nick Diamond found that – as shown in the laboratory – real-world memory search was strongly organized by temporal context, in that jumps tended to move forward in time and to nearby items. Older adults memories were much less temporally organized than younger adults’, even when accounting for the quantity of information retrieved. Moreover, temporal organization predicted the amount of detail people retrieved (as measured by the Autobiographical Interview), showing that the way we search through memory shapes the information that pops into mind (Diamond & Levine, 2020).

For additional research concerning the vividness of free recall in relation to eye movements and individual differences in autobiographical episodic memory, see Armson, Diamond, & Levine (2020).

Research concerning the way people spontaneously jump from one bit of information to another when searching memory has been highly influential in theories of memory, yet this work has been constrained to studies of word lists where the sequences could be controlled and repeated. The degree to which this research generalizes to real-life was unknown.

Using the staged event, Dr. Nick Diamond found that – as shown in the laboratory – real-world memory search was strongly organized by temporal context, in that jumps tended to move forward in time and to nearby items. Older adults memories were much less temporally organized than younger adults’, even when accounting for the quantity of information retrieved. Moreover, temporal organization predicted the amount of detail people retrieved (as measured by the Autobiographical Interview), showing that the way we search through memory shapes the information that pops into mind (Diamond & Levine, 2020).

For additional research concerning the vividness of free recall in relation to eye movements and individual differences in autobiographical episodic memory, see Armson, Diamond, & Levine (2020).

Prospectively collected events ("diary" studies)

|

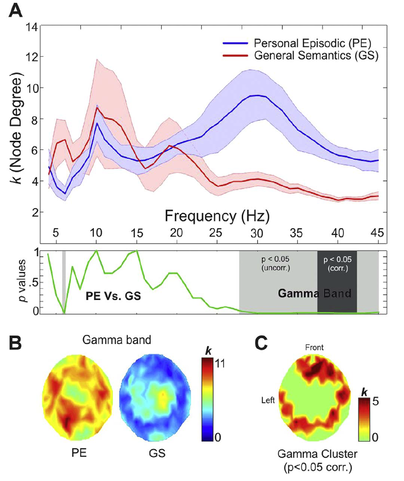

We have sought to increase the fidelity of autobiographical stimulation in neuroimaging research by using a prospective "diary" method whereby participants are scanned during replay of audio recordings that they made contemporaneously with events from their own past. This method allowed for a high degree of control over autobiographical stimuli that cannot be attained with retrospective methods that are previously used in functional neuroimaging studies of autobiographical memory.

Using this method, we have demonstrated distinct networks associated with vivid recall of verified episodic and semantic autobiographical information (Levine et al., 2004) and the effects of memory characteristics including rehearsal and age of autobiographical events on medial temporal lobe activation (Svoboda et al., 2009; Sheldon & Levine, 2013; also see Söderlund et al., 2012). Magnetoencephalography (MEG) data using this paradigm have been used to show how coupling or synchrony of theta oscillations in medial temporal and anteromedial prefrontal regions support subjective vividness in autobiographical recall (Fuentemilla et al., 2014), with followup work focused on cortical gamma synchrony (Fuentemilla et al., 2018). |

The Air Transat study: Autobiographical memory for an airline disaster

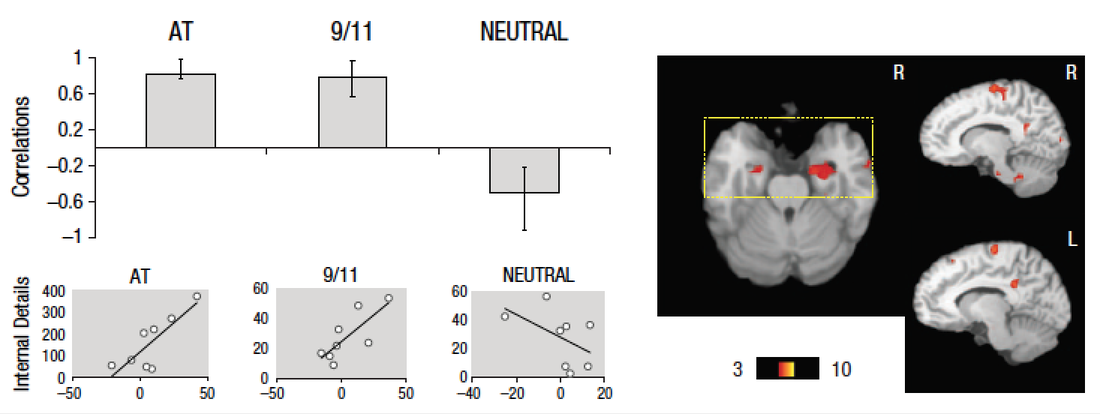

In 2001, Air Transat flight 236 ran out of fuel over the Atlantic Ocean. After 30 terrifying minutes in which the passengers and crew prepared to ditch into the ocean, the pilot miraculously glided the jet to an Azores airbase with no injuries. Our team, including Margaret McKinnon, Daniela Palombo, Rebecca Todd, and Adam Anderson, have studied the effects of this trauma on memory and attention. Using the Autobiographical Interview, we showed that memory for details of the Air Transat disaster was greatly enhanced, but this enhanced vividness was not associated with the presence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD; McKinnon, Palombo et al., 2015). On the other hand, those with PTSD generated an excess of external details. This effect was observed for all events tested, not just the Air Transat disaster, suggesting that strategic control over memory may be altered in those who develop PTSD. These findings may be useful in understanding why some develop PTSD while others do not, even when exposed to the same traumatic event.

We next probed the neural correlates of traumatic memory enhancement in a subset of passengers scanned with fMRI 9 years after the Air Transat disaster (Palombo et al., 2016). Passengers were scanned while viewing video recreations of the event from NBC and the Discovery Channel as part of the media coverage at the time of the event, along with footage of the events of September 11, 2001 and a neutral event. After the scans, passengers' narrative descriptions of the events were scored using the Autobiographical Interview. As in our prior study, passengers showed a strong memory enhancement effect for the traumatic event. The degree of memory enhancement was correlated with activation in the bilateral amygalae, along with medial temporal regions, the ventral visual system, and anterior and posterior midline regions. The same pattern was observed in relation to memory for September 11, 2001. This is the first fMRI study of memory for a life-threatening event in a group of individuals with homogenous traumatic exposure. The correspondence of traumatic memory enhancement with amygdalar activation supports the role of this structure in memory for remotely occurring trauma, and further suggests mechanisms for memory vividness of both traumatic and non-traumatic events.

We next probed the neural correlates of traumatic memory enhancement in a subset of passengers scanned with fMRI 9 years after the Air Transat disaster (Palombo et al., 2016). Passengers were scanned while viewing video recreations of the event from NBC and the Discovery Channel as part of the media coverage at the time of the event, along with footage of the events of September 11, 2001 and a neutral event. After the scans, passengers' narrative descriptions of the events were scored using the Autobiographical Interview. As in our prior study, passengers showed a strong memory enhancement effect for the traumatic event. The degree of memory enhancement was correlated with activation in the bilateral amygalae, along with medial temporal regions, the ventral visual system, and anterior and posterior midline regions. The same pattern was observed in relation to memory for September 11, 2001. This is the first fMRI study of memory for a life-threatening event in a group of individuals with homogenous traumatic exposure. The correspondence of traumatic memory enhancement with amygdalar activation supports the role of this structure in memory for remotely occurring trauma, and further suggests mechanisms for memory vividness of both traumatic and non-traumatic events.

Selected publications

For full publication list, see Google Scholar; articles may be downloaded from the Rotman Research Institute article database

Imaging/ Healthy Adults

Clinical

For full publication list, see Google Scholar; articles may be downloaded from the Rotman Research Institute article database

Imaging/ Healthy Adults

- Petrican, R., Palombo, D., Sheldon, S., & Levine, B. (2020). The Neural Dynamics of Individual Differences in Episodic Autobiographical Memory. eNeuro, 7(2). DOI: 10.1523/ENEURO.0531-19.2020.

- Diamond, N. B., Abdi, H., & Levine, B. (2020). Different patterns of recollection for real-world and laboratory-based episodes in younger and older adults. Cognition, 202, 104309. DOI: 10.1016/j.cognition.2020.104309.

- Diamond, N. B., Armson, M. J., & Levine, B. (2020). The truth is out there: Accuracy in recall of verifiable real-world events. Psychological Science, 31(12), pp. 1544–1556. 2020 Nov 23:956797620954812. DOI: 10.1177/0956797620954812. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33226299.

- Diamond, N. B., & Levine, B. (2020). Linking Detail to Temporal Structure in Naturalistic-Event Recall. Psychological Science, 31(12), pp. 1557–1572. 2020 Nov 23:956797620958651. DOI: 10.1177/0956797620958651. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33226305.

- Fan, C.L, Romero, K., & Levine, B. (2020). Older adults with lower autobiographical memory abilities report less age-related decline in everyday cognitive function. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 308. DOI: 10.1186/s12877-020-01720-7.

- Fan, C. L., Abdi, H., & Levine, B. (2020). On the relationship between trait autobiographical episodic memory and spatial navigation. Memory & Cognition, 49(2), 265-275. DOI: 10.3758/s13421-020-01093-7.

- Armson, M.J., Diamond, N.B., Levesque, L., Ryan, J. D., & Levine, B. (2020). Vividness of recollection is supported by eye movements in individuals with high, but not low trait autobiographical memory. Cognition, 2021, 206, 104487. DOI: 10.1016/j.cognition.2020.104487.

- Selarka, D., Rosenbaum, S., Lapp, L., & Levine, B. (2019). Association between self-reported and performance-based navigational ability using internet-based remote spatial memory assessment. Memory, 27(5):723-728. DOI: 10.1080/09658211.2018.1554082.

- Diamond, N., Romero, K., Jeyakumar, N. & Levine, B. (2018). Age-related decline in item but not spatiotemporal associative memory for a real-world event. Psychology and Aging, 33(7):1079-1092. DOI: 10.1037/pag0000303.

- Petrican, R. and Levine, B. (2018). Similarity in functional brain architecture between rest and specific task modes: A model of genetic and environmental contributions to episodic memory, Neuroimage, 179:489-504. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.06.057.

- Palombo, D., Sheldon, S., & Levine, B. (2018). Individual differences in autobiographical memory. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22(7):583-597. DOI: 10.1016/j.tics.2018.04.007.

- Sheldon, S. & Levine, B. (2018). The medial temporal lobe functional connectivity patterns associated with forming different mental representations. Hippocampus, 28(4):269-280. DOI: 10.1002/hipo.22829.

- Palombo, D.J., Bacopulos, A., Amaral, R.S.C, Olsen, R.K., Todd, R.M., Anderson, A.K., & Levine, B. (2018). Episodic autobiographical memory is associated with variation in the size of hippocampal subregions. Hippocampus, 28(2):69-75. DOI: 10.1002/hipo.22818.

- Fuentemilla, L. Palombo, D.J., & Levine, B. (2018). Gamma phase-synchrony in autobiographical memory: evidence from magnetoencephalography and Severely Deficient Autobiographical Memory. Neuropsychologia, 110:7-13. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.08.020.

- Hebscher, M., Levine, B., Gilboa, A. (2017). The precuneus and hippocampus contribute to individual differences in the unfolding of spatial representations during episodic autobiographical memory. Neuropsychologia. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2017.03.029.

- Sheldon, S., & Levine, B. (2016). The role of the hippocampus in memory and mental construction. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1369(1). 76-92. DOI: 10.1111/nyas.13006.

- Sheldon, S., Amaral, R., & Levine, B. (2016). Individual differences in visual imagery determine how event information is remembered. Memory, 5,1-10. DOI: 10.1080/09658211.2016.1178777.

- Armson, M.J., Abdi, H., & Levine, B. (2016). Bridging naturalistic and laboratory assessment of memory and aging: The Baycrest Mask Fit Test. Memory, 17,1-10. DOI: 10.1080/09658211.2016.1241281.1-10.

- Sheldon, S., Farb, N., Palombo, D., & Levine, B. (2016). Intrinsic medial temporal lobe connectivity relates to individual differences in episodic autobiographical remembering. Cortex, 74, 206-216.

- Sheldon, S., & Levine, B. (2015). The Medial Temporal Lobes Distinguish Between Within-Item and Item- Context Relations During Autobiographical Memory Retrieval. Hippocampus, 25(12), 1577-1590.

- Palombo, D.J., Alain, C., Söderlund, H., Khuu, W., & Levine, B. (2015) Severely deficient autobiographical memory (SDAM) in healthy adults: A new mnemonic syndrome. Neuropsychologia, 72, 105-118.

- Fuentemilla, L, Barnes, G., Düzel, E.*, & Levine, B.* (2014). Theta oscillations orchestrate medial temporal lobe and neocortex in remembering autobiographical memories. NeuroImage, 85(2), 730-7. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.08.029.

- Heisz, J.J., Vakorin, V., Ross, B., Levine, B.,* & McIntosh, A.R.* (2014). A Trade-off between Local and Distributed Information Processing Associated with Remote Episodic versus Semantic Memory. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 26(1), 41-53. DOI: 10.1162/jocn_a_00466.

- Palombo, D.J., Amaral, R.S.C., Olsen, R.K., Müller, D.J., Todd, R.M., Anderson, A.K., & Levine, B. (2013). KIBRA Polymorphism is Associated with Individual Differences in Hippocampal Subregions: Evidence from Anatomical Segmentation using High-Resolution MRI. J Neuroscience, 33(32), 13088-13093.

- Sheldon, S., & Levine, B. (2013). Same as it ever was: Vividness modulates the similarities and differences between the neural networks that support retrieving remote and recent autobiographical memories. Neuroimage, 83, 880-891.

- Söderlund H., Moscovitch M., Kumar N., Mandic, M. & Levine, B. (2012). As time goes by: Hippocampal connectivity changes with remoteness of autobiographical memory retrieval. Hippocampus, 22, 670-679.

- Spreng, R.N., & Levine, B. (2012). Doing what you imagine: Completion rates and frequency attributes of imagined future events one year after prospection. Memory. DOI: 10.1080/09658211.2012.736524.

- Renoult, L., Davidson, P.S.R., Palombo, D.J., Moscovitch, M., & Levine, B. (2012). Personal Semantics: At the crossroads of semantic and episodic memory. Trends in Cognitive Science, 16(11), 550-558. DOI: 10.1016/j.tics.2012.09.003.

- Palombo, D., Williams, L., Abdi, H., Levine, B. (2012) The Survey of Autobiographical Memory (SAM): A novel measure of trait mnemonics in everyday life. Cortex. DOI: 10.1016/j.cortex.2012.08.023.

- Todd, R.M., Palombo, D.J., Levine, B., & Anderson, A.K. (2011). Genetic differences in emotionally enhanced memory. Neuropsychologia, 49, 734-744.

- Svoboda, E & Levine, B. (2009). The effects of rehearsal on the functional neuroanatomy of episodic autobiographical and semantic remembering: a functional magnetic resonance imaging study. Journal of Neuroscience, 29, 3073-3082.

- McKinnon, M. C., Svoboda, E., & Levine, B. (2007). The frontal lobes and autobiographical memory. In B. L. Miller & J. L. Cummings (Eds.), The Human Frontal Lobes, Functions and Disorders (2nd ed., pp. 227-248). New York: Guilford Publications.

- St Jacques, P. L., & Levine, B. (2007). Ageing and autobiographical memory for emotional and neutral events. Memory, 15, 129-144.

- Svoboda, E., McKinnon, M. C., & Levine, B. (2006). The functional neuroanatomy of autobiographical memory: A meta-analysis. Neuropsychologia, 44, 2189-2208.

- Spreng, R.N. and Levine, B. (2006). The temporal distribution of past and future autobiographical events across the lifespan. Memory & Cognition, 34, 1644-51.

- Levine, B., Turner, G.R., Tisserand, D.J., Graham, S.I., Hevenor, S.J., McIntosh, A.R. (2004) The functional neuroanatomy of episodic and semantic autobiographical remembering: a prospective study. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 16, 1633-1646.

- Levine, B. (2004). Autobiographical memory and the self in time: Brain lesion effects, functional neuroanatomy, and life-span development. Brain and Cognition, 55, 54-68.

- Levine, B., Svoboda E.M., Hay, J.F., Winocur, G., Moscovitch, M. (2002). Aging and autobiographical memory: dissociating episodic and semantic retrieval. Psychology & Aging, 17, 677-689.

Clinical

- Seixas Lima, B., Graham, N.L., Leonard, C., Levine, B., Black, S.E., Tang Wai, D.F., Freedman, B., & Rochon, E. (2020). Impaired coherence for semantic but not episodic autobiographical memory in semantic variant primary progressive aphasia. Cortex, 123:72-85. DOI: 10.1016/j.cortex.2019.10.008.

- Seixas Lima, B., Murphy, K., Troyer, A., Levine, B., Graham, N. L., Leonard, C., Tang-Wai, D., Black, S., & Rochon, E. (2020). Language and memory: An investigation of the relationship between autobiographical memory recall and narrative production of semantic and episodic information. Aphasiology, 1-20. DOI: 10.1080/02687038.2020.1843593.

- Seixas Lima, B., Murphy, K., Troyer, A., Levine, B., Graham, N. L., Leonard, C., & Rochon, E. (2020). Episodic memory decline is associated with deficits in coherence of discourse. Cognitive Neuropsychology, 37(7-8), 511-522 DOI: 10.1080/02643294.2020.1770207.

- Renoult, L., Armson, M., Diamond, N., Fan, C., Jeyakumar, N., Levesque, L., Oliva, L., McKinnon, M., Papadopoulos, A., Selarka, D., St. Jacques, P., & Levine, B. (2020) Classification of general and personal semantic details in the Autobiographical Interview. Neuropsychologia, 144, 107501. DOI: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2020.107501.

- Petrican, R., Soderlund, H., Kumar, N., Daskalakis, Z.J., Flint, A., & Levine, B. (2019). Electroconvulsive therapy “corrects” the neural architecture of visuospatial memory: Implications for typical cognitive-affective functioning. NeuroImage: Clinical, 23:101816. DOI: 10.1016/j.nicl.2019.101816.

- Sekeres, M., de Medeiros, C., Decker, A., Bacopulos, A., Skocic, J., Szulc, K., Bouffet, E., Levine, B., Grady, C., Mabbott, D., Josselyn, S., & Frankland, P. (2018). Impaired recent, but preserved remote, autobiographical memory in pediatric brain tumor patients. Journal of Neuroscience, 38(38):8251-8261. DOI: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1056-18.2018.

- Stamenova, V., Gao, F, Black, S.E., Schwartz, M.L., Kovacevic, N., Alexander, M.P. & Levine, B. (2017). The effect of focal cortical frontal and posterior lesions on recollection and familiarity in recognition memory. Cortex, 91:316-326. DOI: 10.1016/j.cortex.2017.04.003.

- Esopenko, C. & Levine, B. (2017). Autobiographical memory and structural brain changes in chronic phase TBI. Cortex. DOI: 10.1016/j.cortex.2017.01.007.

- Palombo, D.J., McKinnon, M.C., McIntosh, A.R., Anderson, A.K., Todd, R.M., & Levine, B. (2016). The Neural Correlates of Memory for a Life- Threatening Event: An fMRI study of Passengers From Flight AT236. Clinical Psychological Science, 4, 312-319.

- McKinnon, M.C., Palombo, D.J., Nazarov, A., Kumar, N., Khuu, W., & Levine, B. (2015). Threat of death and autobiographical memory: a study of passengers from Flight AT236. Clinical Psychological Science, 3, 487-502.

- Söderlund, H., Moscovitch, M., Kumar, N., Daskalakis, J., Flint, A., Hermann, N., & Levine, B. (2014). Autobiographical episodic memory in major depressive disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123, 51-60.

- Söderlund, H., Percy, A., & Levine, B. The effects of electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) on autobiographical memory: a review of the literature (2012). In Zeman, A., Kapur, N., & Jones-Gotman, M. (eds.), Epilepsy & Memory: State of the art. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Levine, B., Svoboda, E.M., Turner, G.R., Mandic, M., & Mackey, A. (2009). Behavioral and functional neuroanatomical correlates of autobiographical memory in isolated retrograde amnesic patient M.L. Neuropsychologia, 47, 2188-2196.

- McKinnon, M. C., Nica, E. I., Sengdy, P., Kovacevic, N., Moscovitch, M., Freedman, M., Miller, B. L., Black, S. E., & Levine, B. (2008) Autobiographical memory and patterns of brain atrophy in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 20, 1839-1853.

- Rosenbaum, R.S., Moscovitch, M., Foster, J.K., Verfaellie, M., Gao, F.Q., Black, S.E., & Levine, B. (2008). Patterns of autobiographical memory loss in medial-temporal lobe amnesic patients. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 20, 1490-1506.

- Söderlund, H., Black, S. E., Miller, B. L., Freedman, M., & Levine, B. (2008). Episodic memory and regional atrophy in frontotemporal lobar degeneration. Neuropsychologia, 46, 127-136.

- Rosenbaum, R.S., Stuss, D.T., Levine, B., and Tulving, E. (2007). Theory of mind is independent of episodic memory. Science, 318, 1257.

- McKinnon, M. C., Svoboda, E., & Levine, B. (2007). The frontal lobes and autobiographical memory. In B. L. Miller & J. L. Cummings (Eds.), The Human Frontal Lobes, Functions and Disorders (2nd ed., pp. 227-248). New York: Guilford Publications.

- McKinnon, M.C., Black, S.E., Miller, B., Moscovitch, M., & Levine, B. (2006). Autobiographical memory in semantic dementia: implication for theories of limbic-neocortical interaction in remote memory. Neuropsychologia, 44(12), 2421-2429.

- Steinvorth, S., Levine, B., & Corkin, S. (2005). Medial temporal lobe structures are needed to re-experience remote autobiographical memories. Neuropsychologia, 43, 479-496.

- Levine, B., Freedman, M. Dawson, D., Black, S.E. & Stuss, D.T. (1999). Ventral frontal contribution to self-regulation: Convergence of episodic memory and inhibition. Neurocase, 5, 263-275.

- Levine, B., Black, S.E., Cabeza, R., Sinden, M., Mcintosh, A.R., Toth, J.P, Tulving, E., & Stuss, D.T. (1998). Episodic memory and the self in a case of isolated retrograde amnesia. Brain, 121, 1951-1973.